You know how people used to say "we only use 10% of our brains"? It's not true, but stay with me. I think most of us only use 10% of our computers. Not because we're not smart enough—because we didn't have access to the translation layer.

I've been thinking about this for a while now. The computer sitting in front of you—and mine—has enormous potential. CPU cycles available. Memory waiting to be used. The ability to process, transform, create, automate. And most of us interact with it by clicking around inside software that someone else built, doing things that someone else decided we should be able to do.

That's not a criticism. That's just how it was. If you wanted to get your computer to do something custom—something specific to your needs—you had to write code. And writing code required years of training, a specific kind of brain, a career path most of us didn't take.

The translation layer was locked.

What Is the Translation Layer?

Code was always just translation: human intention → machine action. You have an idea of what you want to happen. The computer can make it happen. But someone needs to translate between the two.

That's what programmers did. They were the translators. They took what people wanted and converted it into a language the machine could execute.

This is why software companies became so powerful. They employed the translators. If you wanted to get something done with a computer, you either used software they built or you hired your own translator. Most of us just used what was available.

But now AI handles that translation. You can describe what you want in English—plain English—and the machine can figure out how to do it.

That's vibe coding. Talking to your computer to get it to do things for you.

Why Does This Matter Beyond "Tech People"?

This isn't a niche skill for developers. This is the new skill of work, period. There are no "non-technical jobs" anymore—not in the sense that everyone needs to learn to code, but in the sense that everyone needs to learn how to direct their computers to do things for them.

I want to be careful here because I've seen this point get misunderstood.

I'm not saying everyone needs to become a programmer. I'm not saying you need to learn Python or understand algorithms or care about data structures.

I'm saying the distinction between "technical" and "non-technical" roles is dissolving. Because directing a computer used to require technical skills. Now it requires clear thinking and the ability to communicate what you want.

Those are different skills. And they're skills most white-collar professionals already have—they just haven't applied them to their machines yet.

The barrier wasn't capability. It was access.

What Does It Look Like in Practice?

I've started running multiple projects at the same time. One keeps moving in the background while I'm in meetings, doing day-to-day work. I check in, give feedback, keep it going. A year ago that would've required a team or years of technical training I don't have.

Here's what changed for me: I stopped thinking of my computer as a tool I use and started thinking of it as compute I direct.

That sounds abstract, so let me make it concrete.

Before: I would open applications. I would use the features those applications provided. I would work within the constraints that designers and developers had set for me. If I wanted something the software didn't do, I was stuck.

Now: I describe what I want to accomplish. The AI figures out how to make the computer do it. I evaluate the result, give feedback, iterate. The constraints are different. They're about my ability to articulate what I want—not about what software someone else built for me.

I built a browser-based game. I've deployed multiple websites. I've created automation systems that handle workflows I used to do manually. I don't have a CS degree. I still couldn't explain what a for-loop does if you asked me. But I can get my computer to do things I couldn't have done a year ago.

What Questions Should You Be Asking?

I don't have a perfect framework for maximizing compute yet. But I find myself asking new questions: What projects am I not starting because I assumed I couldn't? What's my computer doing right now while I'm in this meeting? What am I leaving on the table?

These questions feel uncomfortable because they reveal something: most of us have been dramatically underutilizing the resources available to us.

Not because we're lazy. Not because we're not smart. Because we didn't have access to the translation layer that would let us direct those resources.

Now we do.

So the questions become:

What would you build if you could easily tell your computer what to do?

Not "what would you build if you learned to code for three years"—that's a different question with a different answer. What would you build if you could just describe it and iterate toward it?

What's your computer doing right now?

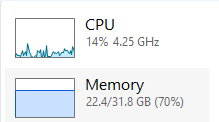

Probably not much. Sitting there. Waiting. CPU mostly idle. Memory mostly free. Meanwhile you're doing work manually that the machine could be doing for you—if you knew how to ask.

What are you leaving on the table?

This is the uncomfortable one. Because the answer is probably "a lot." Projects not started. Automations not built. Tools not created. Not because they were impossible, but because the barrier felt too high.

The barrier is lower now. What does that change?

How Should You See Your Computer Differently?

Look at the computer in front of you. It's not a fixed thing with a set of applications. It's raw power—compute—that you and AI can shape into whatever you need.

This is the perceptual shift I'm trying to point at.

Your computer isn't a collection of software. It's not defined by the applications installed on it. It's not limited to what designers at Microsoft or Apple or Google decided you should be able to do.

It's raw capability. Processing power. Memory. Storage. Network connections. The ability to do things—lots of things, fast, repeatedly, at scale.

What it does with that capability is now, increasingly, up to you.

That's new. For most of human-computer interaction, the answer to "what can my computer do?" was "whatever software you have installed." Now the answer is closer to "whatever you can clearly describe."

What's the Skill to Develop?

The skill isn't coding. The skill is learning to direct compute—to articulate what you want clearly enough that AI can translate it into action, and to iterate when the first attempt isn't quite right.

This is learnable. It's not mystical. It's not reserved for people with certain backgrounds.

It does require practice. You won't be good at it immediately. The first time you try to get your computer to do something through vibe coding, it probably won't work perfectly. You'll need to clarify, iterate, adjust your ask.

That's normal. That's the learning curve.

But the curve is manageable. I've coached over a hundred people through this—non-technical professionals learning to direct their computers to build things. The pattern is consistent: early frustration, gradual clarity, then a moment where it clicks and they realize they can do things they never thought possible.

The barrier was never their intelligence. It was access to the translation layer.

Now they have it. Now you have it.

What Do You Want to Build?

There's no project you couldn't undertake. The formal barriers are gone. The question now is just: what do you want to build?

This is where I want to leave you—not with a framework or a methodology, but with a question.

Look at the computer in front of you. See it differently. Not as a fixed thing, but as raw power waiting to be directed.

What would you do with that power?

What's the project you've been putting off because you assumed you couldn't? What's the tool you wish existed? What's the workflow you've been doing manually that a machine could handle?

The formal barriers are gone. The translation layer is accessible.

The question isn't whether you're technical enough. The question is what you want to create.